The Dissolution of Mumbai Harbour: A Conducive Setting enlists the factors responsible for initiation of port activities in the Mumbai Harbour, emphasizing how anthropogenic interventions have significantly altered the region’s coastline over time. By studying the historical development of the island city, six cases can be identified where its shoreline was drastically reshaped. This article focuses on the first such case: between c. 1650 and 1668 A.D., an era when the bustling metropolis we know today was a humble archipelago of seven agrarian islands.

c. 1650-1668 A.D.: A HUMBLE ARCHIPELAGO OF 7 AGRARIAN ISLANDS

The earliest records of Mumbai as a settlement can be dated back to c. 1650 A.D. An era during which Mumbai was not one but seven separate and amorphous islands.

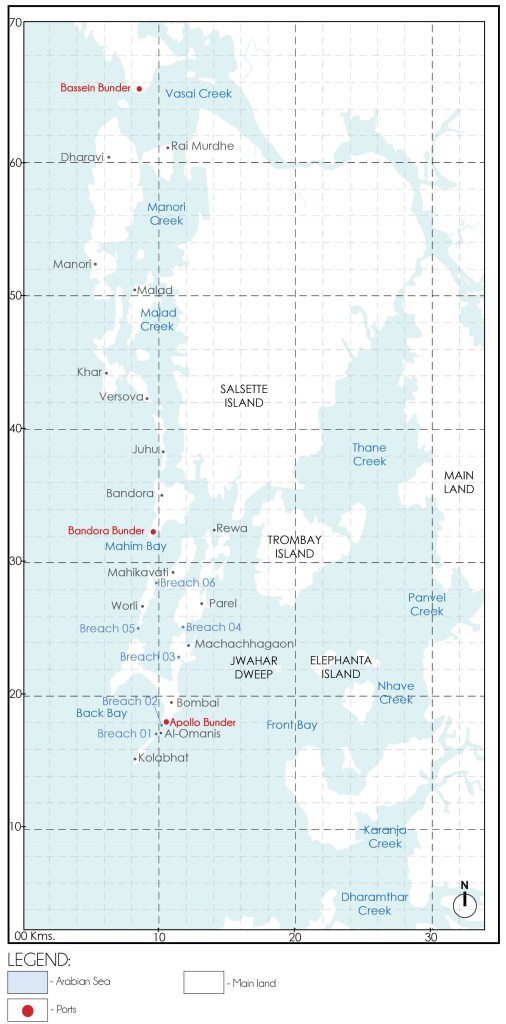

Fig. 01 shows the archipelago of Mumbai. The Southernmost island was a rocky strip of land-the Kolabhat island. Towards the North of the Kolabhat was a triangular shaped rocky landform-the Al-Omanis or island of the deep-sea fisherman.

Moving northwards was a ‘H’ shaped landmass-the original island of Bombai. Towards the North-west of Bombai was another rocky landmass-the island of Worli. Further North of Worli was a sandbar-the island of Mahim

c. 1650-1668 A.D.

Source: Graphics by Author

earlier known as Mahikawati. Towards the North-east of Bombai laid the Machachhagaon island. North of Machachhagaon was a very long uneven landform-the island of Parel.

These islands were inhabited primarily by the Kolis, a native fishing community who depended on the sea for their livelihoods. They engaged in activities such as fishing, boat-making, sea trade, navigation, and salt production—each adapted to the unique character of the local coastline.

The marine conditions varied across the archipelago. The southern islands, especially Kolabhat and Al-Omanis, had rough seas and rocky shores. Moving northwards, the calmer waters provided ideal conditions for harbour development. The earliest known port activities occurred at Padav Bunder, at the southern tip of Bombai island i.e. modern-day Apollo Reclamation.

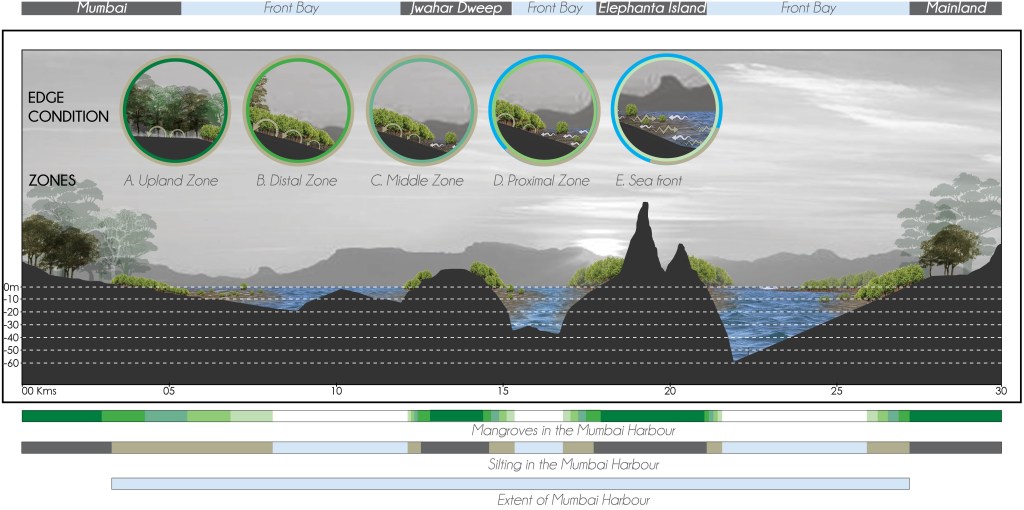

OCEANOGRAPHIC CONDITIONS

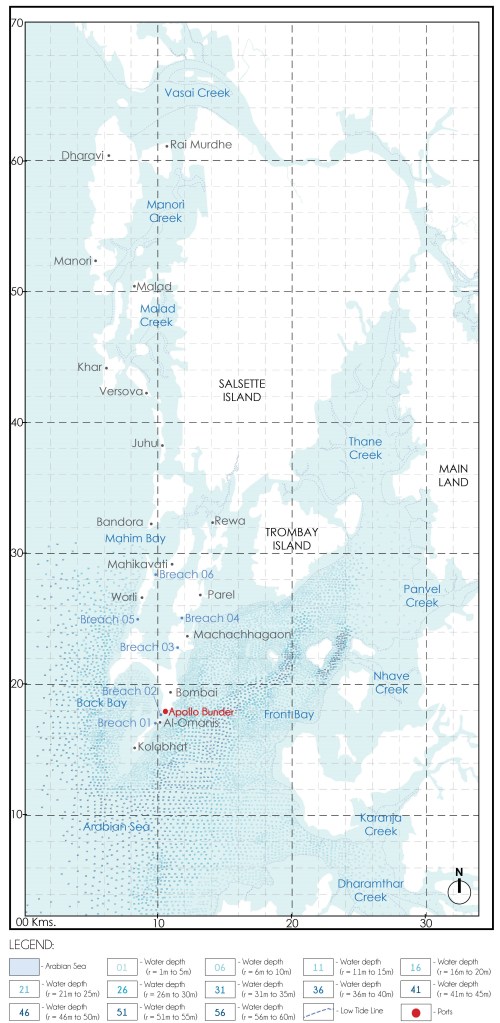

The first recorded bathymetric survey (the measurement of water depth in bodies of water like oceans, rivers, and lakes) of Mumbai Harbour, conducted in 1873 A.D. (Fig. 02), revealed an ocean floor that exhibited a gentle and consistent gradient—sloping approximately 1 meter below sea level near the shoreline to about 60 meters below sea level near Elephanta Island. This natural slope was not abrupt, but rather gradual, providing a stable underwater terrain that was highly conducive to safe anchorage and navigation. Such a bathymetric profile was advantageous for the docking of vessels, particularly during an era when ship designs were still adapting to regional maritime geographies.

TIDAL DYNAMICS

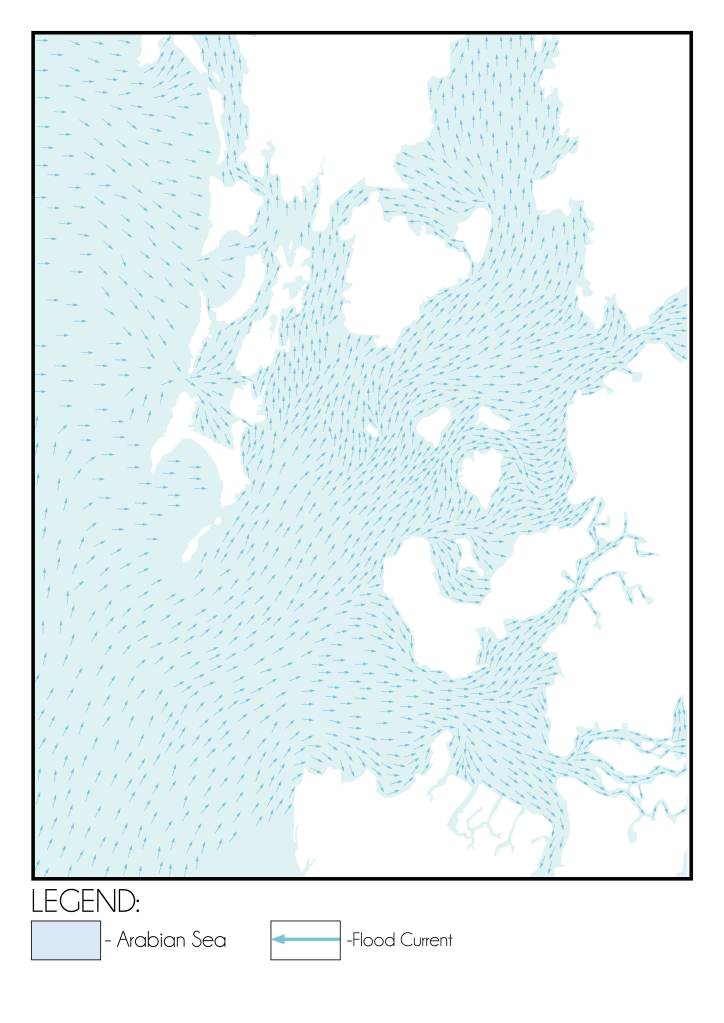

In addition to its favourable ocean floor profile, the Mumbai Harbour was distinctly characterized by the presence of a dual tidal system. Tidal water flowed between the Front Bay (to the east) and the Back Bay (to the west) via natural breaches or channels formed between the original islands of the archipelago. This uninterrupted flow created a dynamic tidal exchange mechanism, playing a pivotal role in the sedimentary and ecological processes of the harbour.

Map showing the flood current direction on the Mumbai Harbour Source: Graphics by Author based on data from Numerical Model Study of Hydrodynamics, Siltation and Wave Tranquility Study for the Navigation of the Dharamtar Creek (Amba River). published by Ministry of water resources, Central Water and power research station, Pune.

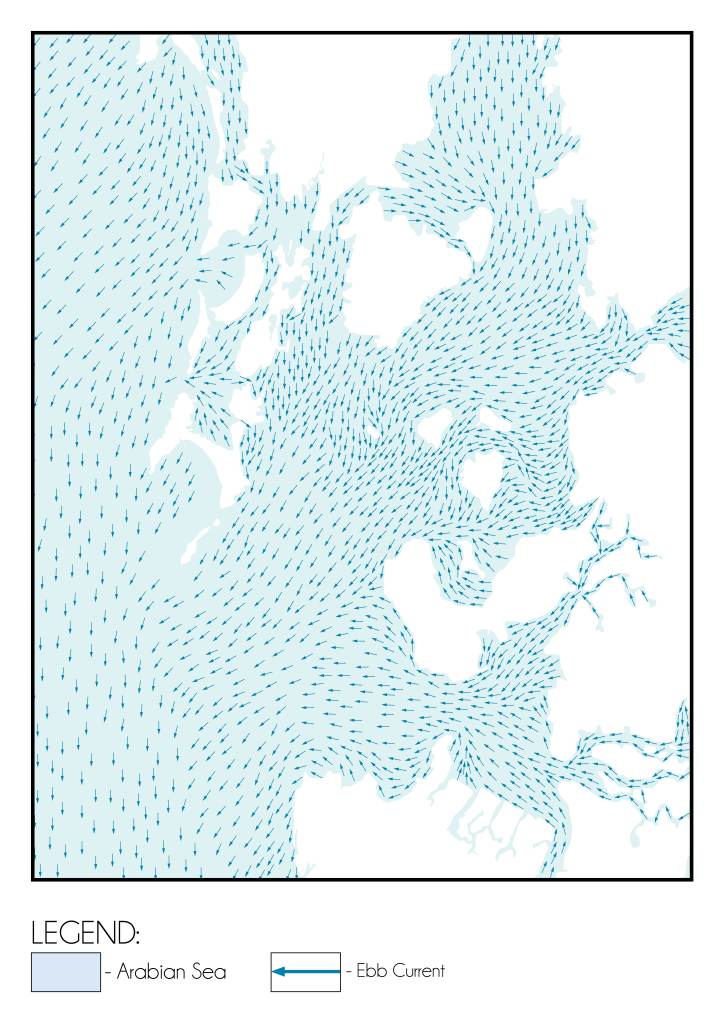

The movement of ebb current in the Mumbai Harbour Source: Graphics by Author based on data from Numerical Model Study of Hydrodynamics, Siltation and Wave Tranquility Study for the Navigation of the Dharamtar Creek (Amba River). published by Ministry of water resources, Central Water and power research station, Pune.

During high tide, flood currents surged into the harbour, carrying with them silt and other suspended sediments from the Arabian Sea (Fig. 03). These flood waters navigated through the interstitial channels between the islands, dispersing fine sediments across the low-lying areas. As the tide receded, ebb currents followed, draining back toward the sea (Fig. 04). However, the force of the ebb tide was not sufficient to fully remove the deposited material. Consequently, a significant proportion of the silt remained trapped in the inter-island regions.

This bidirectional tidal exchange acted as a natural silt regulation system. The constant inflow and partial outflow of sediment-rich water ensured that the bulk of the silt settled in designated zones between the islands rather than being redistributed throughout the wider harbour basin. This phenomenon effectively preserved the depth of the main harbour channels, reducing the risk of silting in navigational areas and thereby contributing to the long-term ecological and operational stability of Mumbai Harbour.

Thus, the tidal dynamics of the region, coupled with its advantageous underwater topography, laid the foundation for the development of a sustainable and naturally regulated port environment during the mid-17th century.

GEOMORPHOLOGICAL PROCESSES AND SILT MANAGEMENT:

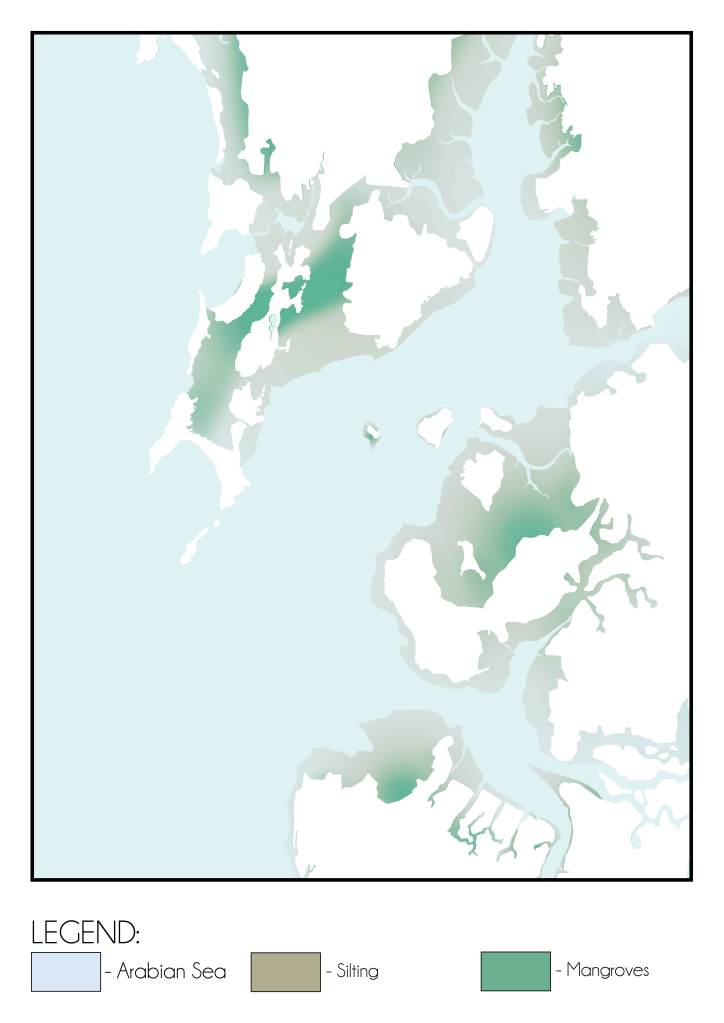

The interplay between tidal dynamics and sediment deposition played a critical role in shaping the inter-island terrain of the Mumbai archipelago. The repeated movement of tidal waters—flooding in during high tide as shown in Fig. 03 and receding during low tide as shown in Fig.04, resulted in the gradual accumulation of fine silt and sediments in the low-lying zones situated between the individual islands as shown in Fig. 05. These areas, being naturally sheltered and relatively calm due to the protective arrangement of the islands, provided an ideal setting for the formation of tidal mudflats.

Silt deposition in the Mumbai Harbour Source: Graphics by Author

Mangrove and mudflat formation due to silt deposition in the Mumbai Harbour Source: Graphics by Author

Over time, these mudflats began to undergo ecological transformation. The moist, nutrient-rich sediment beds became suitable for the establishment of salt-tolerant vegetation, including halophytic grasses and mangrove species as shown in Fig. 06. These pioneer plants were instrumental in trapping additional silt brought in by subsequent tidal movements. Their dense root systems bound the loose sediments together, further stabilizing the ground and reinforcing the physical structure of the mudflats.

As this process continued, the vegetated mudflats acted as natural sediment retention zones, effectively intercepting and arresting silt before it could disperse back into the open harbour. The presence of this vegetative barrier not only prevented the re-entry of silt into the navigable channels but also contributed to a more stable intertidal environment.

This self-regulating geomorphological system served as a natural defence against harbour silting. By retaining sediments within the inter-island flats rather than allowing them to circulate freely throughout the bay, the process helped maintain the water depth essential for port operations. The result was a harbour that required minimal human intervention to remain navigable, thus ensuring its continued functionality and sustainability as a maritime centre during the early phases of its development.

In this way, the synergy between tidal motion, sediment deposition, and ecological succession produced a dynamic yet balanced environment—one that supported both the natural evolution of the coastline and the human use of the harbour as a port.

CONCLUSION:

Four key factors converged to create the conditions necessary for the emergence of port activity in 17th century Mumbai. These factors, deeply rooted in the region’s natural setting, collectively laid the foundation for the city’s eventual rise as a prominent maritime centre. These include:

A. THE STRATEGIC LOCATION OF THE ISLAND CHAIN:

Situated along the western coast of India, the Mumbai archipelago occupied a geographically advantageous position along important Arabian Sea maritime routes. Its location enabled direct access to trading networks connecting the Indian subcontinent with the Persian Gulf, East Africa, and Southeast Asia. The islands, by virtue of their placement, served as a natural waypoint for ships seeking safe harbour and access to inland markets. This strategic orientation allowed early settlers and traders to capitalise on existing commercial flows, thereby fostering the initial stirrings of port-related activity.

B. THE FAVOURABLE BATHYMETRY OF THE MUMBAI HARBOUR:

As evidenced by the bathymetric records of 1873 A.D., the gradual slope of the seabed—from shallow near the shore to deeper zones near Elephanta Island—created an ideal underwater profile for anchorage. Ships approaching the harbour could do so without encountering sudden drops or hidden reefs, significantly reducing navigational hazards. This consistent underwater gradient allowed vessels of varying sizes to anchor safely, supporting the harbour’s development as a reliable and accessible port.

C. THE DYNAMIC TIDAL EXCHANGE BETWEEN THE FRONT AND BACK BAYS:

The natural tidal circulation between the Front Bay and Back Bay further enhanced the harbour’s suitability for maritime activity. The movement of flood and ebb tides through the channels separating the islands facilitated a continuous exchange of water and sediment. This dynamic tidal system not only influenced local hydrology but also contributed to the ecological vitality and sedimentary stability of the harbour. By distributing silt between the islands and regulating its flow, the tidal exchange system helped maintain navigable channels and a self-cleaning harbour environment.

D. THE GEOMORPHOLOGICAL PROCESSES DRIVEN BY SILT DEPOSITION AND VEGETATION GROWTH:

Over time, the deposition of silt in low-lying inter-island areas, combined with the colonisation of these zones by salt-tolerant vegetation, resulted in the formation of tidal mudflats. These mudflats played a key role in retaining sediment and stabilising the shoreline. The natural vegetation acted as a buffer, preventing silt from re-entering the main harbour basin. This process maintained water depth and ensured that harbour operations were not impeded by excessive silting—a critical consideration in the era before modern dredging technologies.

Together, these four interrelated factors—strategic geography, favourable bathymetry, an efficient tidal system, and ongoing geomorphological adaptation—created an environment uniquely suited to the birth and growth of port activity. What began as a scattered cluster of agrarian islands was thus poised to evolve into a vital node of maritime trade, long before large-scale infrastructural interventions took place. While later centuries would see increasing human influence complicating this natural balance, the 17th Century harbour thrived largely due to the convergence of these natural advantages.

Bibliography:

- Input reduction and acceleration techniques in a morphodynamic modeling: A case study of Mumbai harbor; Author: Balaji Ramakrishnan, Niraj Pratap Singh, Satheeshkumar Jeyaraj

References:

- The Rise of Bombay: A Retrospect; Author: S. M. Edwardes Publisher: Times of India Press, Mumbai, 1902

- A Study on the Eastern Waterfront of Mumbai: A Situation Analysis conducted between August 2000 – December 2001; Author: Design Cell: Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute of Architecture and Urban Design Research Institute. Publisher: Urban Design Research Institute, Mumbai, 2001.

- Tides of Time: A History of Mumbai Port; Author: V. M. Kamath Publisher: Mumbai Port Trust, Mumbai.

Author’s Note:

If this topic interests you, explore the category titled the ‘The Dissolution of Mumbai Harbour’ . The published articles under this category include:

- The Dissolution of Mumbai Harbour: An Introduction

- The Dissolution of Mumbai Harbour: A Conducive Setting

- The Dissolution of Mumbai Harbour: Influence of Anthropogenic Activities c. 1650-1668 A.D.

- The Dissolution of Mumbai Harbour: Influence of Anthropogenic Activities c.1668 to 1873 A.D.

- The Dissolution of Mumbai Harbour: Influence of Anthropogenic Activities c.1873 to 1914 A.D.

- The Dissolution of Mumbai Harbour: Influence of Anthropogenic Activities c. 1914 to 1947 A.D.

Leave a comment